Interior Design Faculty Leverage AI for Exploratory Designs

Interior Design Professor Claas Kuhnen advocates for increased and innovative use of technology – including AI – for both interior and industrial design. In March, Kuhnen published an article in the online publication Develop 3D, where he discusses how better integration of hardware and software can democratize the design education process, enabling students with very different skill sets to productively participate and increase their creativity.

In the design disciplines – especially interior design and industrial design – sketching is traditionally seen as the first step of the process, and as faster and more accessible than 3D modeling and rendering. Kuhnen disagrees. For many students, picking up 3D modeling can be faster than the learning curve required to create realistic illustrations. He believes that introducing students to a wide range of software options and platforms can help them find their creative voice more easily.

“As an educator, my task is not to provide an apprenticeship-like experience that forces students through one narrow tunnel of accepted methods and tools,” he writes. “Instead, it is to provide students with a solid general foundation, and then to give them diverse options to further develop their skill sets, based on their own interests, resulting in very unique and individual design personalities.”

Creating Design Workflows with 3D Modeling and AI

Kuhnen’s research focuses on developing unique workflows to help students become more efficient and effective at communicating their ideas. Now, he is adding AI platforms to their toolkits. “It’s amazing to see how — in one year — AI technology has changed. We are all very aware that this is impacting education. By integrating AI, I am breaking with the established steps in the design process to help students be more creative and able to express more ideas more quickly.”

Interior Design Professor Evan Pavka also sees the value for students’ creative development and design criticism. “Just like a sketch or a rendering, these devices and modes of visualization allow designers new ways to look at some of the questions of our discipline,” he says.

Kuhnen is mainly utilizing AI as part of the ideation phase of the design process. The objective in this phase is to generate a wide range of ideas, working toward a concept that is unique and new and not iterative. He sees AI as a better resource than sourcing images because a well-trained AI can generate a wide variety of options or ideas. “When students are in an ideation phase or making a mood board, they often go to Google Images or Pinterest and look for inspirational images,” he says. “The problem, especially with Pinterest is that it is an algorithm that learns you and becomes biased towards your interests– feeding you what you like and not pushing you in new directions. And it is really important for students to be pushed outside of their comfort zone.”

Kuhnen is careful to call the AI-generated results “options,” “ideas,” or “visions.” He says, “I don’t want to call these ‘solutions,’ because ‘solutions’ feels like it’s finished. I see AI as a great brainstorming tool in addition to what we normally do. It’s a thinking tool; a way to start a discussion. There is a lot of design work that needs to also happen to get to an actual solution that works.”

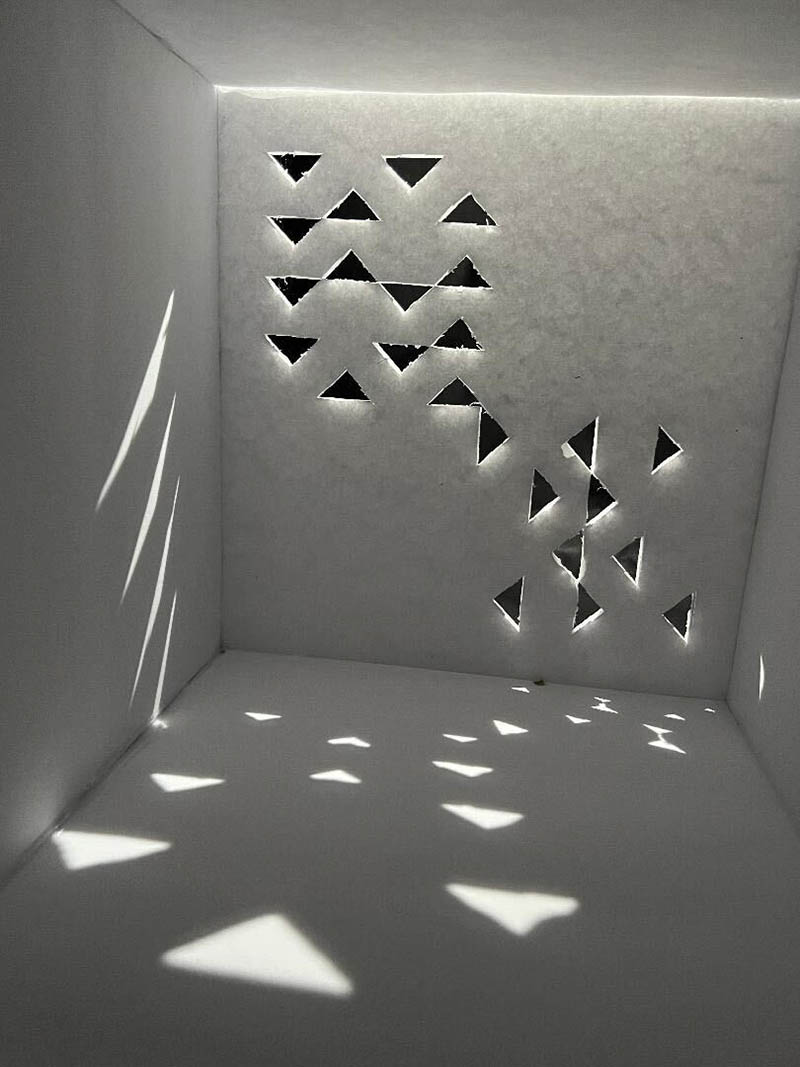

By its very nature, AI’s “random” generations encourage the students to collaborate with the platform, he adds. “There are happy accidents and interesting discoveries. It’s fascinating because it is not perfect. It’s fuzzy. It has flaws that require students to invest time and develop their own problem-solving abilities. As an instructor, I know that the student can’t just do something in 15 minutes and call it great work.”

There is another value inherent in working with “fuzzy” ideas at the front-end of a design process, either AI generated or not, Pavka adds. “Pragmatically, showing clients a finished rendering can be very scary, because it presents this idea that the thing is fixed and immovable. Something that’s looser or a bit more abstract can be a better tool for dialogue and exploring ideas with a client,” he says.

Testing AI Platforms

Kuhnen is experimenting with several different online Stable Diffusion-based web services including Playground.ai, Leonardo.ai, DreamStudio, Lexica.art, and Vizcom.ai. He says that each have their strengths and weaknesses, are being developed at different speeds, and offer different implementations of popular AI image-based tools. Developed and released by Stability AI in 2022, Stable Diffusion is a deep learning, text-to-image model used to generate detailed images based on text descriptions or inputted images.

Stable diffusion works by taking the pixels that make up an image and adding layers of noise to it, which is then saved to a database. The noise is then understood as patterns. A database of millions and millions of images is needed to build up the understanding of the AI. When the user writes a prompt, the AI reverses the noise, creating a new image made from pixels sourced from countless images. The images will often look mushy and unclear, but with enough refinement steps, they can become clearer. Kuhnen is not that interested in focusing on prompt engineering. “Some people might write a whole page of prompts and really guide it, but that is not really how we are using it,” he says.

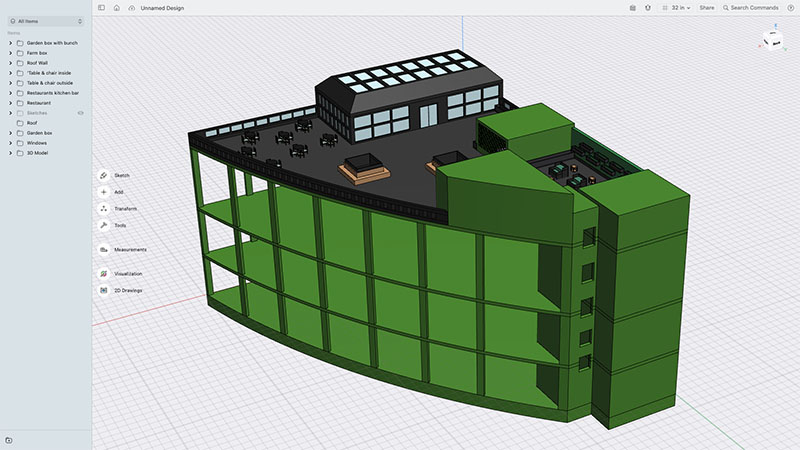

Using Leonardo.ai and a ControlNet module together, Kuhnen shares an example that begins with a hand-drawn, line-art sketch of an architectural interior space. The AI uses the scribble preprocessor that uses the line drawing to understand the desired composition, and then fills in color and shading based on text prompts. A user can also take a screenshot of a rendered 3D model, use other preprocessors that find the hard edges or depth data of the rendered space or object, and adjust elements and characteristics based on prompts. “For example, you can take a very generic-looking SketchUp model, and then make it look like a classic, or contemporary, or Japanese-inspired image,” he says. “You can even train an existing Stable Diffusion model with specific images of brands, and it can reproduce those images in new ways that feel branded.”

Using Leonardo.AI, Kuhnen shows how the user can input an image of a space, circle certain parts of the image, and add or take away features (such as a window, fireplace, lighting fixture, furniture, etc.) The image is re-rendered seamlessly into the new composition. It “may not be absolutely perfect, but this is a great shortcut compared to traditional compositing. We’re not artists, we are designers; and design students need tools that make them more productive and efficient – tools that can help them tell the story fast. It’s a very competitive industry, and these tools can save a designer so much time,” he emphasizes.

Kuhnen has noticed that students are a bit more fearless and willing to try new things with the help of AI. For example, “incorporating human figures into architecture spaces is always a tricky thing. Now you can take a 3D rendering, and mask an area where you want to have a human figure, and the AI can render in the human figure. It can also make the human figure match the style of architectural space; for example, if you are designing something very futuristic, you also want the figure to look like it is in the future. Or if the architecture is very organic, you may want the outfit of the figure to show some of these organic elements, too. You would have had to be a master at Photoshop to have done that before.”

Positioning AI as a Tool vs. a Threat

“AI is not a tool for cheating, it’s just a different tool,” says Kuhnan. He compares it to developments in Photoshop. When using early iterations of the software, designers had to rely on the time-consuming clone and blend tools. Now, Photoshop includes the healing brush, which creates the same effect almost automatically. “When we think about the improvements in Photoshop, or any other software, we don’t want to go bac.kwards like it is the ’90s. This argument is just as bad when we consider AI.”

Pavka adds, “It reminds me of a lot of the discussions in the 1980 and 1990s when designers were trying to see if they could design a building from an Excel spreadsheet, and the idea of computers making architecture or designing any other object. We have been evolving to work with algorithms and new instruments for a long time. These devices and programs are really just a means to an end.”

Like Kuhnen, Pavka sees AI for its collaborative potential, rather than a threat to the design profession. “The acceleration is interesting, as a way of thinking about how we work and how we collaborate,” he says. “I’m not worried about AI or Chat GPT, because if our students were to use those tools, it would help them professionally. We can think of AI as a collaborator and an interlocutor. Even in the academic world, there’s a lot of discussion about how we can think of AI as a resource of knowledge.”

Still, Pavka is “cautiously suspicious” of its full application due to the fundamental difference between visual perception and the human experience of existing in a space. “If we emphasize the primacy of visuality in design, then design is simply a kind of active vision. The relationship is then about looking rather than a more embodied nature of the experience — the scale of a space and the relationship to the body. AI designs are created by a machine that will never actually experience, think, or feel,” he says.

AI-generated imagery is only a small piece of the puzzle of what it takes to design a space, Pavka adds. “We should think of these images as conveyor of meaning, emotion, atmosphere, or effect rather than a representation of the final project,” he says. “These are a way of articulating ideas that will change with site conditions, material changes, budgetary changes, etc.” He points out that while consumer-facing platforms as simple as the Ikea Kitchen Planner exist and eliminate some need for a designer, designers are still trained to understand space, flow, and functionality.

Furthermore, design is only one part of what it takes to make a building. “If we are honest with ourselves,” Pavka says, “architecture and interior design represents only about 10% of the entire building industry.” AI could change the role of design imagery in the larger process of where design meets the build. “I don’t necessarily worry that design will be replaced, but I do wonder if it removes the critical space of the image in the design process. Even an orthograph — a plan, a section, and elevation — is embedded with meaning. It’s a kind of magical thing where we agree that a set of abstract lines can represent something. There’s a kind of a covenant that we enter into with these images, and that commitment has to be in question, because the space is never going to actually look like that. The paper image is still a kind of fiction where the actual space is what is real. These flashy renderings are not reality.”

Pavka feels that, relative to AI-produced images, it is imperitive that designers advocate for themselves, promoting the unique value they bring to the process. “A big developer probably doesn’t care that much about someone’s sketches,” he says. “I don’t know how much the people who are funding these kinds of projects really care about the tools we are using. They're [simply] looking at how these designs are vehicles of bigger development ideas and goals.”

Ultimately, Pavka and Kuhnen are working together to make their students “critically aware of the tools that they have, and the ways that they can deploy, hack, and re-appropriate those tools, whether they’re analog or digital,” says Pavka. “I think there're many things that you can do with very simple programs and still deploy an interesting voice.”

Beyond WSU, Kuhnen has been conducting workshops at Bissell, 2B Design Studio, Akers Architectural Rendering, and universities around the world, including UCLA, Universidad de Monterrey in Mexico, and Germany’s University of Regensburg and Universität Hamburg. “The organizations and people who are asking for these workshops are very curious about learning about this. This is also how I know that my own students are on the cutting edge. This will help them keep pace with industry.”

Sources:

https://develop3d.com/opinion/comment/new-directions-giving-students-new-design-tools/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stable_Diffusion

https://stability.ai/