Faculty Spotlight: The Art Department Welcomes Historian of Islamic Art, Dr. Yasemin Gencer

Art Historian Dr. Yasemin Gencer has joined the department as a Pre-Faculty Fellow. Gencer is the author of numerous articles on printing and the early Turkish Republican popular press. She publishes the research and translation blog Today in 1920s Turkey, which she is currently compiling into a book. Her English translation of Celal Nuri’s Hatem ül-Enbiya (1914), an Ottoman Turkish scholarly monograph on the life of the Prophet Muhammad is forthcoming and will be published by Edinburgh University Press (2025). Gencer has been teaching Islamic Art History courses at Wayne State University since Fall 2020 and recently received a General Education Teaching Award for her Islamic Art and Architecture course.

Art Historian Dr. Yasemin Gencer has joined the department as a Pre-Faculty Fellow. Gencer is the author of numerous articles on printing and the early Turkish Republican popular press. She publishes the research and translation blog Today in 1920s Turkey, which she is currently compiling into a book. Her English translation of Celal Nuri’s Hatem ül-Enbiya (1914), an Ottoman Turkish scholarly monograph on the life of the Prophet Muhammad is forthcoming and will be published by Edinburgh University Press (2025). Gencer has been teaching Islamic Art History courses at Wayne State University since Fall 2020 and recently received a General Education Teaching Award for her Islamic Art and Architecture course.

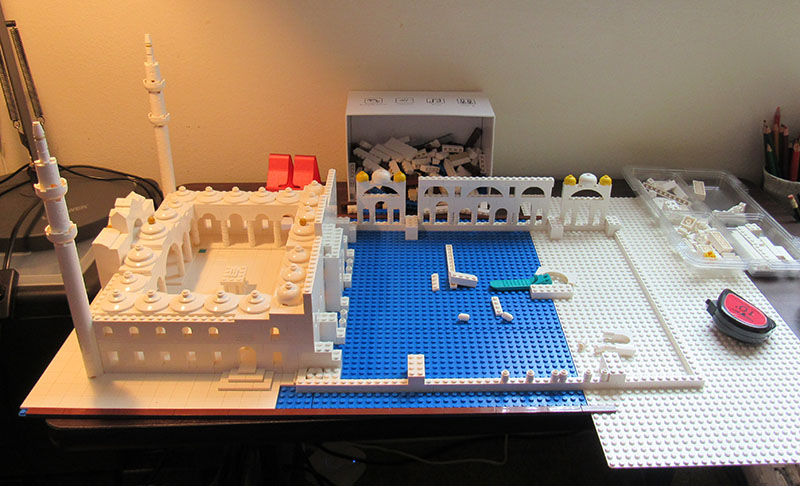

Making Art History Interactive … With Legos®

Gencer is quick to share her passion for creating Islamic architecture replicas with Legos® – a hobby that results in great instructional tools. She appreciates the unique way that Legos® enable one to experience architecture. “We can be hands on with book arts, with ceramics, things that are much more portable, but with architecture, we are mostly working off of PowerPoint slides,” she says. “Working with Legos® gives me insight into architecture that I never had before. I'm not an architectural historian, and I mostly deal with smaller and more ephemeral objects. This gave me an entirely new appreciation for architectural forms and how they are constructed.”

Her Lego® buildings are developed from scratch, necessitating a great deal of planning as well as trial and error. She works from photographs and floorplans that she can find, either through academic sources or just through Google. Gencer documents some of her process, and keeps the “blueprints” that she creates on graph paper. “Teaching Islamic art classes had a significant impact on my interest in architecture,” she says, “Something like a simple, centrally-planned tomb with a dome on top, for example, looked easy to build. But far from it!”

In the future, Gencer hopes to offer a class that combines Art History and Lego® construction. “We can understand architecture so much better through this miniature medium,” she says. “So much experimentation is required. You build up, and then it doesn't fit with the other parts, and you have to take it all down and start over.” She says that building with Legos® also teaches project management. “Sometimes, I could be halfway through a build and need to order new parts; that can take months! I’ve had to stop my build waiting for materials to arrive, which I’m assuming was not that different in Byzantine Constantinople, when they’re waiting for a column to emerge from a quarry or an obelisk to arrive from Egypt. So, it’s given me this interesting, practical insight into those ever-present challenges of resources and project management.”

Capturing 1920s Turkey

One of Gencer’s research projects utilizes 1920s periodicals. An interest in ideological shifts at the infancy of the Turkish Republic in 1923 led to her examination of political cartoons in periodicals and satirical gazettes published at that time. “When you’re researching using periodicals,” she says, “you don't read them from cover to cover, because they are so abundant. You’re kind of flipping through them.” She created a blog to have an outward-facing, accessible outlet for her discoveries. “Every day that I was reading though these periodicals, I would take whatever I would find interesting and provide the original Turkish text as well as an English translation. Then, I would comment on it and contextualize it and problematize certain things. After approximately 200 posts, I finally understood where my monograph needed to go! The blog gave me the opportunity to develop so many ideas and work out what I wanted to write about. It also became a method of leaving breadcrumbs for myself, to track my process and provide leads for future research projects. For instance, a theme emerged from several blog posts which blossomed into an article.”

The research now centers on photography contests that were being published by the gazettes at this time. “I started seeing these pages of people’s faces, especially in the illustrated gazettes. I realized that these were competitions for readers to send in their pictures, and thought it would be a great project to data mine and learn more about the people who read the magazines I was studying. Contemporary photograph sharing is so pervasive, it’s not that interesting, however knowing that the practice or impetus to share photographs publicly goes back more than 100 years is very exciting.” She adds, “Not everything we work on as Art Historians is fun or positive or joy inducing. But this project is one thing that, every time I present it, brings smiles to people’s faces.”

Gencer surmises that the photograph-sharing competitions were a way for the gazettes to get to know their readership and gather information about them. She explains, “One of the illustrated gazettes published a coupon that included questions about preferences alongside their initiative. They were essentially profiling their readership.” The photos also provide an opportunity for insight into how readers were presenting themselves to each other. “People were presenting themselves with ‘modern’ appearance that supported their roles as viable citizens of the new Turkish Republic,” she explains.

What Gencer finds most compelling about the contests was how the newspapers were using photograph sharing to create community, as social media platforms do today. “The coolest part about this is the back and forth between the paper and the readers. The readers would send in their pictures, for instance, and then, if they didn't see them published, some of them would complain and then the newspaper would respond to them alongside the next batch of pictures. Evidently, several of the initiatives were so popular there was a queue of people waiting for their pictures to be published. This is excellent information for a qualitative analysis, because there’s a give and take. The publisher has a responsibility towards the reader, because they don’t want to upset and/or lose their readership!”

Translating Celal Nuri’s Hatem ül-Enbiya

Gencer is in the final editing stages of her translation of Celal Nuri’s Hatem ül-Enbiya. Nuri (1881-1938) was a journalist, writer, and politician and one of the main people whose ideas influenced the early Turkish Republic. She started translating the book in 2017, after completing her PhD. It is a labor of love. “A colleague, Dr. Monica Ringer from Amherst College, asked if I would be interested in translating bits of this monograph,” she says. “I read the first chapter and fell in love, and I decided to translate the entire 326-page book.

“What made me fall in love with this book was that, in the first chapter, the author, who is a Turkish Muslim scholar, places himself at the Acropolis in Greece. He’s waxing poetic about the reconstruction and restoration activities at the Parthenon, and the history and what it’s been through, how it was built to honor this Goddess of Wisdom, and the various trials and tribulations that have afflicted the monument since. He sets up the book with Art History and Archaeology and the scientific method, and argues that this is the approach needed to better access the identity and history of the Prophet Muhammad.”

What is compelling to Gencer is how the author attempts to close his mind off to his own religiosity and Islamic identity and approach his analysis as a mathematician. He engages with post-Enlightenment and modern research methods spearheaded by European historians, and drawing from archeology, psychology, and even the theory of evolution. “He was one of the first Muslim scholar to do this,” says Gencer. “It breaks a lot of records in that way.”

The book has significance for Islamic researchers today, Gencer says. “Nuri is dabbling in all of these ideas that were really new at the time. In doing this, he is trying to inject some new energy into the religion and consider it within a modern context and demonstrate the ways that Islam — as a product of the 7th century — can translate to the 20th century and still be relevant. He argues that Islam can’t be incompatible with modernity because that would be a death sentence. I think this is why researchers today are going to want to read this. It's going to be a great resource for anyone who is interested in modernization processes from within the Islamic world.”

Building Community in the Classroom

Gencer feels that what is most important to her teaching is communication, accessibility, and translation – meaning translating ideas from a scholarly language to a language that an undergrad student can better understand. “As art historians, a lot of times we’re translating images and objects into words and ideas. Communication and accurate representation are important parts of translation.” One way she does this is to focus on breaking down terminology and forms that might otherwise be unfamiliar or intimidating.

She wants to encourage students that Islamic Art History is accessible to everyone, even if you don’t know Arabic script. “When I started learning Islamic art and specializing in it, I didn’t know how to read the Arabic script, but it didn’t hinder my ability to appreciate or understand it. That’s also something I bring to my classroom with my students. I’m like ‘I get it.’ I remember when this just looked so abstract. I tell them to not worry about the text, because I'll tell them what it says. ‘Let’s focus on the context, the history, the form,’ I say. I won’t leave them in the dark.”

It is also important for her to build a sense of community in the classroom. This comes from personal experience. “When I started college in the United States, I was fresh out of a Turkish high school, so I carried a huge burden to understand the culture of an American classroom. I missed a lot of communication. My students may also be bringing similar experiences to the classroom. They may have graduated from a high school that’s not in the United States or their school may not have had any art classes or art history classes. I’m very aware of the diversity of experiences that people bring into my classroom.”

As a Pre-Faculty Fellow, Gencer hopes to develop a broader curriculum that focuses on Islamic art. “I want to build out a sustainable, robust curriculum that emphasizes informative, accessible, and relevant approaches to the study of art history in general and Islamic art in particular,” she says. “I look forward to being more hands-on in those types of decisions.”

LINKS:

https://cfpca.wayne.edu/art/profile/hg3551

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celal_Nuri_%C4%B0leri

https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/khamseen/closed-captioning/2021/on-closed-captions-access-and-teaching/